Interagency Paralysis: Stagnation in Bosnia and Kosovo — Vicki J. Rast and Dylan Lee Lehrke

INTRODUCTION:

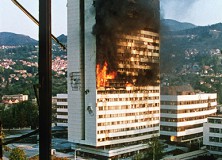

U.S. government security practices and structures proved ineffective in managing the bitter intra-state conflicts, complex emergencies, and ethnic cleansing associated with the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo. An examination of the Washington’s response to these is highly relevant to the Project on National Security Reform (PNSR) because they heralded many characteristics of the post-Cold War security environment that continue to challenge U.S. interagency processes. Among others, these features include applying alliances beyond Cold War missions and conducting humanitarian interventions and other complex contingency operations.

STRATEGY:

The U.S. government failed to develop a coherent strategy in the first three years of the Bosnian war. Instead, an ad hoc, reactive stance allowed the belligerents to control the tempo of events. Although the Kosovo approach was developed increasingly within the interagency process, the strategy nonetheless failed to adequately integrate force and diplomacy.

INTEGRATED ELEMENTS OF NATIONAL POWER:

Prior to Operation Deliberate Force and the Kosovo War, U.S. policies did not integrate diplomatic and military might. Force and diplomacy were eventually coordinated in Bosnia, but with difficulty and in a halting manner. In Kosovo, elements of national power were also inefficiently coordinated, turning what should have been a quick war into a drawn out and unproductive endeavor.

EVALUATION:

The U.S. response in Bosnia and Kosovo was weak primarily due to the lack of integrated analysis and planning between the diplomatic corps and the military. The State and Defense Departments proceeded from a shallow analysis, based on the assumption that the war resulted from atavistic ethnic hatred, and developed policy options centered on protecting departmental equities. Consequently, officials presented the president, Bill Clinton, with policies that could not be integrated.

Even when the National Security Council (NSC) dictated a strategy, the State and Defense Departments could not cooperate well due to their disparate perspectives on desired goals. Another shortcoming in the U.S. strategy was that no individual beneath the president could navigate the full political-military spectrum with authority and competency. In Bosnia and Kosovo, moreover, the military improperly interfered in political decisions and diplomats meddled in military matters. This led to tremendous tensions between State and Defense. In the Balkans, the absence of an official who could effectively manage, or at least understand, force and diplomacy proved detrimental to operations. In both Bosnia and Kosovo, effective management and implementation often resulted from ad hoc organizations and fait accompli decisions.

RESULTS:

The interagency struggle eroded Washington’s ability to take decisive action, reduced the credibility of American power, and made it difficult for Washington to lead the global response to the crisis. This impotence prolonged the Balkan crises very likely increasing its human and financial costs. In addition, collective security as a concept and NATO as an organization suffered serious blows. Even after U.S. officials decided to take action in Bosnia and Kosovo, the gap between diplomats and war fighters produced a policy that could not link political and military means and ends. Thus, Washington was able to end the wars but not establish a stable end-state, leaving problems (especially unresolved ethnic and international tensions) for U.S. national security policy that persist to this day.

CONCLUSION:

The U.S. government failed to develop a coherent strategy in the first three years of the Bosnian war, primarily due to a lack of integrated analysis and planning between diplomats and the military. As a result, the interagency process did not formulate policies for presidential consideration in an effective manner. The President received options that were both too few and too contradictory. This led to an ad hoc, ever-changing policy, most often characterized as “muddling through.”

Eventually, the NSC bypassed the interagency process to create a strategy. However, once the policy had been determined, the Departments of Defense and State struggled with implementation, which required the coordination of force and diplomacy. Many of these features also typified Washington’s handling of the Kosovo situation, demonstrating a poor learning curve despite the imperative of responding effectively to one of the most serious national security challenges confronting the United States during the 1990s.